AI in Emergency Medicine Supporting, Not Replacing

Artificial intelligence in medicine has a long history. Back in 1971, INTERNIST-1 was developed. It was, according to the study, the first artificial medical consultant. INTERNIST-1 used search algorithms to diagnose patients. Then, in the 1980s, systems like DXplain and MYCIN further demonstrated that artificial intelligence can support doctors and nurses.

However, today’s advanced AI solutions offer a lot of support. From analyzing large amounts of data to helping with routine tasks and administration. This frees up medical staff time, but also reduces the pressure that is also increased by the reduced number of healthcare workers. The World Health Organization estimates that by 2030, the EU will have a shortage of 4.1 million health workers.

The fact is that artificial intelligence has a lot to offer, not only in terms of relieving the burden on the system, but also on medicine itself. But the question is whether artificial intelligence is actually more accurate or reliable compared to human medical staff. Can the experience and clinical judgment of doctors and nurses surpass human abilities in diagnosing and caring for patients? Or, for instance, in determining the degree of urgency of patient admission, also known as triage.

AI vs. Medical Staff in Patient Prioritization in ERs

According to some data, about 25% of the population visit the emergency room (ER) each year, and the number of those who end up receiving hospital treatment through emergency admission is much higher. In this process, triage, the assessment and prioritization of patients based on the urgency of their condition, is of great importance. For example, it can make a difference whether a patient has a fracture or just a scratch, a persistent high fever, or a simple case of sneezing. However, these decisions are not always easy, as even something that seems minor, such as a needle stick or a cut, can be dangerous and require a tetanus vaccine.

The European Society of Emergency Medicine was founded more than 30 years ago, in 1994, in London. Their mission is to advance research, education, practice, and standards in the specialty of emergency medicine across Europe. They also organize congresses that bring together more than 3,500 participants from over 80 countries. The 2024 congress was held in Copenhagen, and this year’s event took place in Vienna. It was at this congress that Dr. Renata Jukneviciene, a postdoctoral researcher at Vilnius University in Lithuania, presented the results of the study addressing this very question. Together with her colleagues Eva Naktinyte and Aida Emilija Balukonyte, she explored the potential of artificial intelligence to support patient triage.

Fifty-one nurses and six physicians were given anonymous questionnaires to complete. They all worked in the emergency department of a university hospital. The study authors then randomly selected clinical cases from a pool of 110 cases retrieved from the PubMed database and divided them into five triage categories, ranging from the most urgent to the least urgent. The questionnaire was completed by 44 nurses and all six physicians. The same cases were also analyzed using artificial intelligence.

The results

The measurement included several key indicators. Sensitivity refers to the ability to recognize emergencies, while specificity shows how well non-emergencies are recognized. In addition, the accuracy gives the overall precision of the classification, and the positive and negative predictive values show how accurate the labeled emergencies and non-emergencies really are.

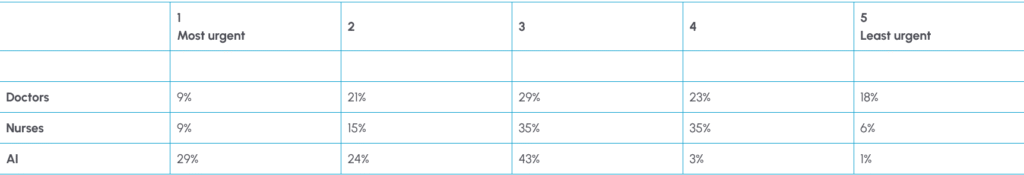

Overall accuracy, which shows how well the system or person correctly assigns patients to the right category, was 70.6% for doctors, 65.5% for nurses, and 50.4% for AI. The distribution table shows only how often each evaluator used each category; it does not reflect accuracy. Therefore, although AI assigned patients to the most urgent category more frequently than nurses (27.3% vs. 9.1%), this indicates only a labeling tendency rather than greater accuracy. AI did not outperform the nurses in this regard. However, in subsequent analyses focusing on therapeutic cases, AI’s overall accuracy in category assignments was higher than that of nurses, although it still did not reach the level of accuracy achieved by physicians. The positive predictive value, or the probability that patients marked as urgent are actually urgent, was 76.7% for doctors, 76.9% for nurses, and 68.1% for AI. The negative predictive value, or the probability that patients marked as non-urgent are actually not urgent, was 51.2% for doctors, 36.5% for nurses, and 17.0% for AI.

These results indicate that, although artificial intelligence cannot replace medical staff, it could provide significant support in situations such as staff overload. However, in a press release, Dr. Jukneviciene stated that careful integration and human oversight are crucial, and that hospitals should approach AI implementation with caution while focusing on training staff to critically interpret AI recommendations.

Dr. Jukneviciene: AI for Support, Not Substitution

The study showed that AI can be useful as an aid, but not as a replacement. To what extent could this combination reduce the pressure on healthcare staff, given the workload and shortage of healthcare workers in Europe? Could it provide significant help? Are hospitals adopting this type of assistance quickly enough for medical staff to feel relief?

Dr. Jukneviciene: In theory, AI could take over the initial layer of triage by pre-sorting or flagging potentially urgent patients. This could reduce pressure on nurses and shorten waiting times. If AI had access to individual health records, it could make more accurate triage decisions and identify the risk factors specific to each patient. AI has the potential to personalize medicine rather than simply following a generic algorithm. However, at this stage, AI is not accurate enough, raising concerns about safety, patient privacy, accountability, and other issues. While the potential for AI in triage exists, it remains more of a future possibility than an immediate solution to staff shortages.

AI seems to recognize potentially life-threatening patients more cautiously and more often compared to nurses. I am interested in this because, in cases where a nurse encounters a patient for the first time, AI could have an advantage and provide support. In this way, it could also help nurses who are just starting their careers. However, one should be careful not to rely too much on AI. How can we find the right balance?

Dr. Jukneviciene: Yes, absolutely. AI could serve as a valuable second opinion, especially for less experienced staff. AI doesn’t get tired, distracted, or anxious, which means it can provide reassurance when a junior nurse is unsure. However, there is a risk of over-reliance on AI. The key is to use AI as a decision-support tool, not as a replacement. The nurse should always make the final call, but AI can highlight red flags or suggest caution when urgency might be underestimated. Training and clear guidelines will be essential in this context.

In which shift do you think AI could help the most—for example, at what time of day—and what should be the next step?

Dr. Jukneviciene: From a practical perspective, AI could be most helpful during peak hours and night shifts, when emergency departments are understaffed and fatigue affects human decisions. Even simple automated pre-triage could help reduce the bottleneck at the front door. As for the next step, the most important thing is to train AI on real-world hospital data rather than theoretical cases. Only then will it reflect the actual local patient population, and we can start to see the true potential and start to gradually integrate it into our hospital settings.

Human Expertise Remains at the Heart of Medicine

Artificial intelligence has made significant advances in medicine, starting with pioneering systems like INTERNIST-1 in 1971. Today, AI has the potential to ease the pressure, especially given the projected shortage of millions of healthcare workers in Europe by 2030. Despite decades of technological advances, medical staff remain indispensable; the core of medicine has not changed – it is human expertise. Artificial intelligence is a useful tool, and its greatest value lies in enhancing, not replacing, the work of medical professionals, who remain at the heart of patient care.

Credit: Dr. Renata Jukneviciene