Study: Energy policy-making in the EU between past and present

Speed-read:

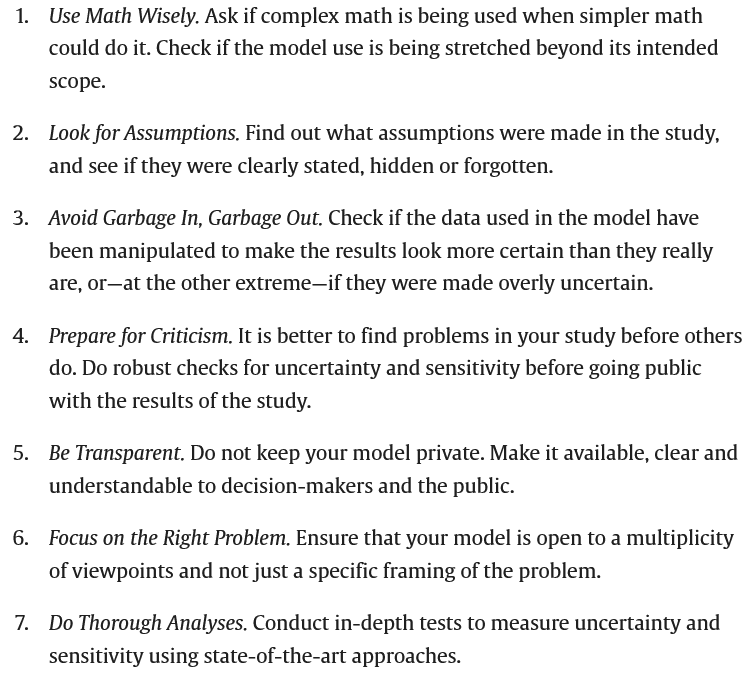

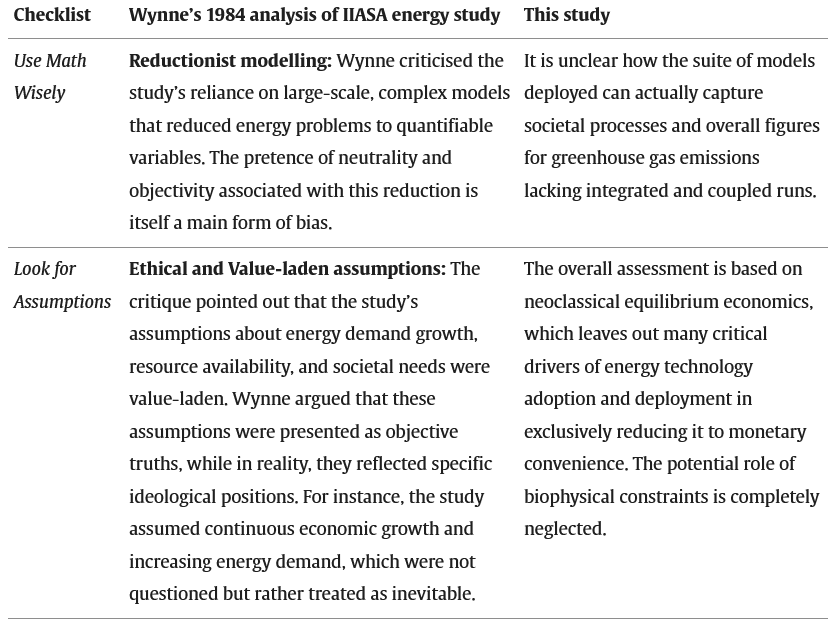

- The authors compare two cases in the field of energy: one from the 1980s, criticized by sociologist Brian Wynne, and a recent one from 2024, prepared by the European Commission for setting greenhouse gas reduction targets by 2040. The analysis uses the method of sensitivity auditing (SAUD), a checklist that evaluates how models handle uncertainties, assumptions, and problem framing, and how transparent and accountable they are for policymaking.

- The study shows that despite four decades, little has changed: models are still used to confirm predetermined policies rather than for critical analysis.

- The topic was chosen due to its academic intrigue, its critical relevance to contemporary societal challenges, the unique opportunity for historical comparison, and our commitment to improving the interface between science and policy.

- By drawing parallels between Wynne’s 1980s critique of IIASA and our analysis of the 2024 European Commission IAR, the study underscores that the lessons from past controversies have not been fully learned. It serves as a reminder that a critical, reflexive approach to modeling is not a new concept but a long-standing necessity.

- Until there is a fundamental shift in understanding—from viewing models as purely technical instruments to recognizing them as socio-technical artifacts embedded in power relations and normative choices—the issues flagged by Wynne will continue to affect modeling practices.

- Academic literature, particularly from the sociology of quantification, provides the intellectual tools to critically engage with these new technologies. It reminds us that technology is never neutral and that its application in policy must be guided by principles of transparency, accountability, participation, and a deep understanding of its social and ethical implications.

- Apply the SAUD checklist rigorously to models used for crisis prediction and management.

- By highlighting the enduring nature of issues first identified decades ago, we hope to impress upon policymakers the importance of learning from historical critiques and integrating these lessons into contemporary practices, especially as new technologies like AI emerge.

It has been more than thirty years since the European Union began to systematically shape energy policy. One of the key moments in this process was the 1995 Energy White Paper, which defined the guidelines for a common energy policy, emphasizing security of supply, market competitiveness, and sustainability. Over the past thirty years, the European Union has faced many challenges, including dependence on energy imports, integrating renewable energy sources, and improving energy efficiency, and political decisions have been essential in addressing all of these issues.

To understand how certain political decisions might affect energy systems and the environment, energy models—computer or mathematical simulations—play an important role by providing predictions and analyses. However, Brian Wynne, a sociologist of science, criticized one such model in 1984, showing that although these models often appear “scientifically precise,” they can be problematic in practice.

In the new study, Energy policy-making in the European Union between past and present, researchers Samuele Lo Piano and Andrea Saltelli explored this topic. Using tools from the sociology of quantification, the authors compare Wynne’s case to the 1980s and the European Commission’s 2024 Impact Assessment Report (IAR), prepared to guide the 2040 greenhouse gas emissions targets. The study applies a method called the Sensitivity Audit (SAUD), a checklist designed to test the transparency and reliability of models used in policy.

We spoke with the corresponding author, Samuele Lo Piano. He is currently an Assistant Professor at the Faculty of Management and Economics, Gdańsk University of Technology, Poland. His research interests include modeling in the fields of energy and sustainability, uncertainty assessment, modeling and evaluation of knowledge quality, the ethics of quantification, and sensitivity analysis.

About the study

This study uses the approach of the sociology of quantification. That is a research field that examines how numbers and statistical data shape society, support or challenge knowledge, and have an impact through their effective and technical content.

They compare two cases in the field of energy: one from the 1980s, criticized by sociologist Brian Wynne, and a recent one from 2024, prepared by the European Commission for setting greenhouse gas reduction targets by 2040. The analysis uses the method of sensitivity auditing (SAUD), a checklist that evaluates how models handle uncertainties, assumptions, and problem framing, and how transparent and accountable they are for policymaking. Wynne criticized the study for the lack of model interconnection (models did not exchange data to create a complete picture) and for creating a false impression of objectivity. Wynne pointed out that modeling is not neutral because it reflects political and social interests and can serve more to justify existing policies than to genuinely inform decisions.

As noted in the study, “Wynne’s analysis made clear that science for policy is never purely objective, as it is shaped by institutional and cultural assumptions that are too often concealed.” And then, the authors examined the European Commission’s 2024 impact assessment for 2040 (IAR) greenhouse gas emissions targets, comparing the findings with Wynne’s critique of the IIASA study from the 1980s.

Applying this checklist to the IAR revealed similar problems as in the IIASA study: the models are not sufficiently integrated, assumptions are one-sided and politically biased, uncertainties are minimized to create a sense of certainty, and the impacts of different policies are not clearly presented. The study also does not identify winners and losers (which social groups benefit or lose from a policy), nor does it take social and ethical aspects into account. One of the key issues is the “state of exception,” meaning that models in policy have special epistemological authority (special power to be believed accurate) and are used ritualistically or rhetorically, more to justify policies than to inform real decisions.

The study shows that despite four decades, little has changed: models are still used to confirm predetermined policies rather than for critical analysis. The study concludes that mathematical models remain important tools in policy, but they must be transparent, open to revision, and complementary to other approaches to avoid ritualistic use (using models only for formal justification) and to ensure that policy is based on genuinely informed and socially responsible decisions.

Choosing the Topic and Its Relevance

Why did you choose this topic?

Samuele Lo Piano: We chose this topic for several compelling reasons, rooted in both academic interest and a deep concern for effective and just policy-making in the face of urgent global challenges. The central motivation was to investigate a persistent paradox. Despite widespread acknowledgment of technical and methodological problems in policy modeling, these models continue to hold immense sway in decision-making. The quality of policy decisions in these areas has profound implications for ecological sustainability, economic stability, and social justice. Understanding how these decisions are informed (or misinformed) by quantitative models is therefore of paramount importance.

The opportunity to draw a direct comparison between Brian Wynne’s seminal critique of IIASA’s energy modeling in the 1980s and a contemporary, high-stakes European Commission impact assessment for 2040 GHG targets was a unique and powerful aspect. This allowed us to assess whether lessons from past controversies have been learned and to highlight the enduring nature of certain systemic issues. Our expertise lies in the sociology of quantification (especially Andrea’s – my coauthor, mentor, and continuous source of inspiration), a field uniquely positioned to critically examine how numbers and statistical data shape society, support or challenge knowledge, and exert influence through their performative and technical content. Applying this lens allowed us to uncover the deeper institutional and political dynamics at play beyond purely technical evaluations.

Ultimately, our motivation is to contribute to better science for policy. In summary, the topic was chosen due to its academic intrigue, its critical relevance to contemporary societal challenges, the unique opportunity for historical comparison, and our commitment to improving the interface between science and policy.

How can this study serve as a guide for creating more transparent, robust, and socially relevant models that better support real-world decisions in energy and climate policy?

Samuele Lo Piano: Our study serves as a critical guide by highlighting persistent shortcomings and advocating for specific remedies. It offers a roadmap for improving modeling practices in several ways. Emphasizing Sensitivity Auditing (SAUD). The systematic application of the SAUD checklist provides a practical framework for scrutinizing models. By rigorously applying SAUD, policymakers and model developers can proactively identify hidden assumptions, biases, and uncertainties, thus enhancing transparency and robustness.

By drawing parallels between Wynne’s 1980s critique of IIASA and our analysis of the 2024 European Commission IAR, the study underscores that the lessons from past controversies have not been fully learned. It serves as a reminder that a critical, reflexive approach to modeling is not a new concept but a long-standing necessity. Understanding these historical patterns can prevent their repetition.

The study strongly advocates for pluralistic and participatory methods, such as participatory modeling, scenario workshops, and extended peer review. These approaches directly address the social relevance of models by integrating diverse perspectives and values, ensuring that models reflect broader societal concerns rather than just technical or economic ones. Our research encourages a shift from using models to justify decisions to using them to genuinely inform and explore policy options. It promotes a culture where models are seen as aids to thought, not substitutes for deliberation.

The study encourages critical reflexivity among modelers and policymakers about the inherent values and assumptions embedded in models. It promotes an understanding that models are not neutral tools but mediate between theories and the world, perpetuating specific institutional or policy agendas if not critically examined. In essence, our study guides the creation of better models by providing both a diagnostic tool (SAUD) and a set of prescriptive approaches (pluralism, participation, transparency) rooted in the sociology of quantification.

Gaps in knowledge and political biases

This question is important for the future of Europe because it relates to how decisions about energy and climate will be made, which directly affect ecological sustainability, economic stability, and social justice. That’s why I’m interested in whether there are enough studies like this and where the gaps in knowledge lie.

Samuele Lo Piano: The way decisions about energy and climate are made directly impacts ecological sustainability, economic stability, and social justice. These are not separate domains but deeply interconnected, and flawed decision-making processes, particularly those relying on potentially biased or opaque models, can have profound and long-lasting negative consequences across all three. For instance, policies based on incomplete models might fail to achieve climate targets, lead to unjust distribution of costs or benefits, or destabilize economies reliant on unsustainable energy systems. While there is a growing body of academic literature within the sociology of quantification and science and technology studies that critically examines the role of models in policy, studies that directly apply frameworks like SAUD to contemporary, high-stakes policy documents (like the European Commission’s IAR for 2040 targets) are still relatively scarce.

Our paper contributes to filling this gap by offering a direct, comparative analysis that highlights the persistence of these issues over decades. There is a need for more empirical, in-depth analyses of how models are actually used in various policy contexts, moving beyond theoretical critiques.

A significant gap lies in understanding how to effectively implement the recommended pluralistic and participatory approaches within existing bureaucratic and political structures. The rise of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in modeling introduces new complexities. There is a gap in understanding how AI-driven models might exacerbate or mitigate the issues of hidden assumptions, opacity, and bias, and how SAUD or similar frameworks need to be adapted for AI systems.

While our study focuses on energy policy, similar issues likely exist in other policy domains (e.g., health, finance, social welfare). More cross-sectoral studies are needed to understand common patterns and unique challenges in the use of models across different policy areas. Despite calls for greater transparency and stakeholder engagement, the divide often persists. Further research is needed on effective mechanisms for translating academic insights into actionable policy changes and fostering genuine dialogue between modelers, policymakers, and the public. More longitudinal studies tracking the evolution of modeling practices and their impact on policy outcomes over extended periods would provide deeper insights into the effectiveness of proposed reforms. Our study serves as a call to action, emphasizing that critical engagement with modeling practices is not an academic luxury but a democratic imperative for Europe’s sustainable and just future.

This means that complex models of energy and climate policies often hide assumptions, minimize uncertainties, and may be politically biased. In other words, policies should not be made solely based on models but must also include social, ecological, and ethical aspects. How would you recommend integrating social, ecological, and ethical aspects into energy and climate policies, given the political biases and uncertainties in models that you have identified?

Samuele Lo Piano: Our study, by applying Sensitivity Auditing (SAUD) to both historical (IIASA, 1980s) and contemporary (European Commission IAR, 2024) cases, demonstrates that complex energy and climate policy models frequently hide assumptions, minimize uncertainties, and are indeed susceptible to political biases. This leads to a situation where models are often used to confirm predetermined policies rather than genuinely inform decisions, creating a “state of exception” where their epistemological authority is used ritualistically. Policies should unequivocally not be made solely based on models. Models are powerful tools, but they are representations of reality, embedded with values and assumptions. Therefore, it is crucial to integrate social, ecological, and ethical aspects into energy and climate policies. We recommend the following approaches for better integration.

Incorporate qualitative data, expert judgment from diverse fields (sociology, ethics, ecology), and real-world case studies. This ensures a broader understanding of the policy context and potential impacts. Actively involve a wide range of stakeholders—including citizens, civil society organizations, industry representatives, and affected communities—in the model development and scenario-building processes. This helps surface diverse perspectives, values, and local knowledge, making models more relevant and legitimate. It can also help identify potential winners and losers of policy interventions, which models often omit.

Broaden the review process for models and impact assessments beyond technical experts to include social actors, ethicists, and environmental scientists. Make models, their underlying data, assumptions, and limitations fully transparent and accessible to the public and to independent scrutiny. This includes clearly stating all assumptions (even implicit ones), acknowledging uncertainties, and detailing potential biases.

Ensure that policy assessments explicitly include social justice, equity, human well-being, biodiversity, and ecosystem services as key metrics, not just economic efficiency or technical feasibility. This might require developing new indicators and methodologies that go beyond traditional cost-benefit analyses. Foster a culture within policymaking institutions that encourages continuous learning, critical self-reflection on modeling practices, and a willingness to revise approaches based on past errors and new insights.

By adopting these recommendations, policy-making can become more robust, equitable, and genuinely responsive to the complex challenges of energy and climate change, moving beyond a narrow, technocratic focus.

Economic Integration, Climate Change, and Security of Supply

“Over the last 60 years, energy policy-making in the European Union has been driven by the pursuit of economic integration, as well as by events such as the first oil crisis and further challenges like environmental pollution and climate change.” In your view, which were the most important?

Samuele Lo Piano: Based on the historical context provided in our paper and broader understanding of EU energy policy, I would identify the following as the most important drivers, often interacting and reinforcing each other. Economic Integration and the Single Market. This is arguably the most fundamental and continuous driver. The European project itself began with the European Coal and Steel Community, aiming to prevent conflict through economic interdependence. The pursuit of a single energy market, promoting competition, security of supply, and efficiency across member states, has been a constant underlying objective since the inception of the EU. This driver often prioritizes economic efficiency and market mechanisms in policy design.

Security of Supply. Major geopolitical events, especially the 1970s oil crisis, profoundly shaped EU energy policy. These events highlighted the extreme vulnerability of European economies to external energy shocks and spurred efforts towards diversification of energy sources, strategic reserves, and reducing dependence on single suppliers. More recently, geopolitical tensions (e.g., with Russia) continue to underscore this driver, pushing for energy independence and resilience.

Environmental Protection and Climate Change. While initially less prominent, concerns about environmental pollution and, more recently and powerfully, climate change, have become paramount. The scientific consensus on climate change and the EU’s commitment to global climate action (e.g., Paris Agreement, European Green Deal) have transformed energy policy. While economic integration provides the structural framework, the oil crises acted as critical catalysts, forcing a strategic re-evaluation of energy security. However, the emergent and increasingly dominant challenge of climate change has fundamentally reshaped the entire landscape, pushing for a transformative agenda that often requires significant interventions in the market and a redefinition of energy security beyond mere supply to include sustainable supply.

Therefore, I would rank them as: Economic Integration (foundational), Climate Change (transformative and current dominant), and Security of Supply (critical response to external shocks).

Until there is a fundamental shift in understanding the issues flagged by Wynne will continue to affect modeling practices

Many of the issues flagged by Wynne in his case study discussed in are still affecting modeling practices and the impact-assessment culture of the European Commission in its energy policy-making. Why? What do you think is the biggest omission, or perhaps the main gap in understanding?

Samuele Lo Piano: The persistence of issues flagged by Wynne in the 1980s in contemporary European Commission modeling practices is a central finding of our study and points to a deep-seated challenge in the science-policy interface. The “why” is complex, but several factors contribute. Large institutions like the European Commission often develop established routines, methodologies, and ways of thinking. Once a particular approach to modeling and impact assessment is embedded, it becomes difficult to change, even in the face of critiques. There’s an institutional comfort with quantitative models that provide seemingly definitive answers, fitting well into existing decision-making structures.

As our paper discusses, models often acquire a “state of exception”—a special epistemological authority that makes them less subject to critical scrutiny. They are used ritualistically or rhetorically, primarily to legitimize or justify policies that may have already been decided upon, rather than to genuinely inform the decision-making process. This “policy-based evidence” approach means that the purpose of modeling shifts from exploration to legitimation. The technical complexity of modern energy system models makes them difficult for non-experts (including many policymakers) to fully understand and scrutinize. This opacity can inadvertently shield hidden assumptions and biases from critical review, allowing shortcomings to persist. Policymakers often operate under pressure to present clear, decisive policy options. Acknowledging high levels of uncertainty or explicit political biases in models can complicate policy narratives and undermine perceived authority.

The lessons from past critiques, like Wynne’s, are either not effectively integrated into institutional learning processes or are dismissed as academic concerns rather than practical imperatives.

In my view, the biggest omission or main gap in understanding is the failure to fully grasp and integrate the inherently normative and socio-political nature of models and scientific advice in policymaking. Models are not neutral, value-free tools; they are social constructs that embody specific theoretical frameworks, assumptions, and values. The omission is the persistent belief, or at least the performative presentation, that models can provide purely objective, technical answers that are separate from political and social considerations. This overlooks the framing of the problem; how a problem is defined (e.g., energy transition as an economic optimization problem vs. a socio-technical transformation) inherently shapes the model and its outcomes.

Until there is a fundamental shift in understanding—from viewing models as purely technical instruments to recognizing them as socio-technical artifacts embedded in power relations and normative choices—the issues flagged by Wynne will continue to affect modeling practices.

Neglected academic literature in the age of artificial intelligence

“Academic literature has a crucial role to play in this context: by recalling past errors, it can help ensure they are not repeated.” At a time when decisions are made with the help of AI, is academic literature being neglected, and if we do not take past mistakes into account, what are the risks?

Samuele Lo Piano: You are correct that academic literature, particularly from fields like the sociology of quantification, plays an indispensable role in providing critical historical context and theoretical frameworks to understand and improve policy-making.

There is a significant risk that academic literature, especially critical and reflective scholarship, can be neglected in the rush to adopt new technologies like AI. Policymakers and institutions might prioritize perceived efficiency, speed, and predictive power of AI models over the slower, more nuanced, and often critical insights offered by academic research. The allure of advanced computational tools can overshadow the foundational lessons from decades of research into the limitations and social embeddedness of quantitative methods. The risks of neglecting past mistakes, particularly in an era of AI-assisted decision-making, are amplified. If past mistakes regarding hidden assumptions and biases are not addressed, AI systems can automate and scale these biases, making them harder to detect, challenge, and rectify.

If AI-driven decisions are not transparent, understandable, or subject to robust public and expert review, it can erode democratic accountability. An uncritical embrace of AI can lead to misplaced trust and over-reliance on its outputs, even when those outputs are based on flawed data, biased algorithms, or an inadequate understanding of the real-world context.

If the data reflects historical biases or incomplete understandings (e.g., neglecting social or ecological dimensions), AI will simply reproduce and potentially amplify these “garbage in” issues, leading to “garbage out” at an unprecedented scale. Without the critical lens provided by academic fields like ethics, philosophy of science, and sociology, AI applications in policy could inadvertently lead to outcomes that violate fundamental ethical principles.

Academic literature, particularly from the sociology of quantification, provides the intellectual tools to critically engage with these new technologies.

The current energy challenges in Europe, and the blackout in Spain

Considering the current energy challenges in Europe, or the blackout in Spain, how would you assess the role of models in predicting and managing such crises? What lessons from your research could help improve actual policy implementation?

Samuele Lo Piano: The role of models in predicting and managing energy crises, such as the hypothetical blackout in Spain, is complex and multifaceted. While models are indispensable, our research suggests that their current application often falls short, potentially exacerbating vulnerabilities rather than mitigating them. Models are crucial for simulating grid stability, forecasting demand and supply, assessing infrastructure resilience, and evaluating the impact of various operational scenarios. They can help identify potential bottlenecks, system weaknesses, and interdependencies that could lead to a crisis. For instance, detailed network models are essential for understanding cascading failures in an electricity grid.

However, our research highlights significant limitations. Crises are inherently characterized by high uncertainty and unpredictable events (e.g., extreme weather, sudden infrastructure failures, geopolitical shocks). Models often struggle to adequately capture and represent these “unknown unknowns,” tending to minimize uncertainties to present a false sense of certainty. Many crisis models are purely technical, focusing on physical infrastructure and energy flows. They often omit critical socio-technical aspects, such as human behavior during a crisis, public response to warnings, the political economy of energy markets, or the social vulnerability of different populations. A blackout, for example, is not just a technical failure but a profound social disruption.

Models used for crisis management might embed assumptions about system resilience, market responses, or policy interventions that do not hold true under extreme stress. Different models (e.g., economic, technical, social) are often not sufficiently integrated, leading to a fragmented understanding of the crisis (if that kind of integration can be achieved at all in a quantitative model…). Therefore, while models provide valuable insights, an over-reliance on them without critical scrutiny can lead to a false sense of security and inadequate preparedness for complex, real-world crises.

Our research offers several critical lessons for improving policy implementation in the context of energy crises. Energy crises are classic “post-normal science” situations: facts are uncertain, values are disputed, stakes are high, and decisions are urgent. Policy implementation must move beyond a purely technical, predictive approach to one that acknowledges these complexities. This means focusing on robust decision-making under uncertainty rather than seeking illusory certainty.

Apply the SAUD checklist rigorously to models used for crisis prediction and management. It would help identify where models might be overstretching their scope or harboring hidden biases that could lead to flawed crisis responses. Involve a diverse range of experts and stakeholders (including emergency services, social scientists, community leaders, and vulnerable populations) in the development of crisis scenarios and response plans. Participatory modeling and scenario workshops can help identify a wider range of risks, vulnerabilities, and effective mitigation strategies that purely technical models might miss.

Policymakers must be transparent about the limitations and uncertainties of models used in crisis management. Clear communication of risks and the probabilistic nature of predictions can build public trust and facilitate more adaptive and resilient responses, rather than fostering panic. Crisis planning models must explicitly incorporate social vulnerability assessments, ethical guidelines for resource allocation during emergencies, and considerations of equity in recovery efforts. A “blackout” is not just a technical event; its impacts are disproportionately felt by vulnerable groups. Establish mechanisms for continuous learning from past crises.

By addressing fundamental issues, energy and climate policies in Europe can become more resilient

On the question of what changes or improvements he would like this study to achieve, he said: “We hope to foster a greater degree of critical self-reflection within institutions like the European Commission regarding their modeling practices. We advocate for the systematic and rigorous application of Sensitivity Auditing (SAUD) as a standard practice in all impact assessments and policy analyses that rely on quantitative models. We seek a shift towards a culture where models genuinely inform and explore policy options, allowing for a more open and adaptive decision-making process.”

He hopes to see a significant increase in the adoption of pluralistic and participatory methods, such as participatory modeling, ‘what-if’ workshops, and extended peer review. Their study seeks to promote greater transparency regarding model assumptions, data, and limitations, making them accessible and understandable to a broader public.

“By highlighting the enduring nature of issues first identified decades ago, we hope to impress upon policymakers the importance of learning from historical critiques and integrating these lessons into contemporary practices, especially as new technologies like AI emerge. In essence, we aspire for our study to contribute to a more robust, democratic, and effective science-policy interface, where models serve as tools for genuine societal progress rather than instruments for legitimizing the status quo. We believe that by addressing these fundamental issues, energy and climate policies in Europe can become more sustainable, equitable, accountable, and resilient,” concludes Lo Piano.

Image courtesy of Samuele Lo Piano/Energy modeling