Canadian Students Facing Hate in University Spaces

Although research exists on hate and freedom of expression, scientists emphasize that academic work specifically focusing on experiences of hate within Canadian universities is limited. The last national study on this topic was conducted in 2011. The aim of the new study, published in early January, was to understand the experiences of Canadian university students with hate, both online and offline.

The authors of the study It happens more than once: Understanding Canadian university students’ experiences of hate, online and offline are Arunita Das, Ghayda Hassan, Monyka L. Rodrigues, and Brianna Comeau.

“Since 2020, and heightened during the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a spike in reports of hate-motivated activity within universities across Canada. However, the experiences of hate by university students continue to remain under-researched and underdeveloped in Canada,” the scientists wrote in the study.

594 students participated in the survey

For the purposes of the study, universities in British Columbia, Alberta, Ontario, Quebec, and Nova Scotia were selected, and a total of 594 students participated in the survey. Participants were either current students or had graduated within the past two years, and they had attended both online and in-person classes. Data were collected between May 1 and June 17, 2022, and the survey development process took four months. The survey contained 34 questions and was anonymous, allowing students to freely share their experiences. Survey questions covered experiences of hate online and in-person, who expressed the hate, the context and form of the incident, emotions after the incident, impacts on academic performance and health, and the university’s responses to reported incidents.

More than 90% of students experienced some form of hate

Results showed that 65% of students experienced hate both online and in-person, 17% only online, slightly less than 13% only in-person, while 5% of students reported experiencing no form of hate. Regarding the sources of hate, students most frequently reported hate from other students, while the second most reported group was university staff, such as cafeteria or administrative personnel. The least reported incidents came from faculty members. Analysis of the spaces in which hate occurred showed that, among 352 participants who reported online hate (out of 594), the most common settings were during classes and in group chats on social media with classmates. Students most often reported hate directed at ethnicity, perceived race/skin color, gender identity/expression, and certain aspects of physical appearance.

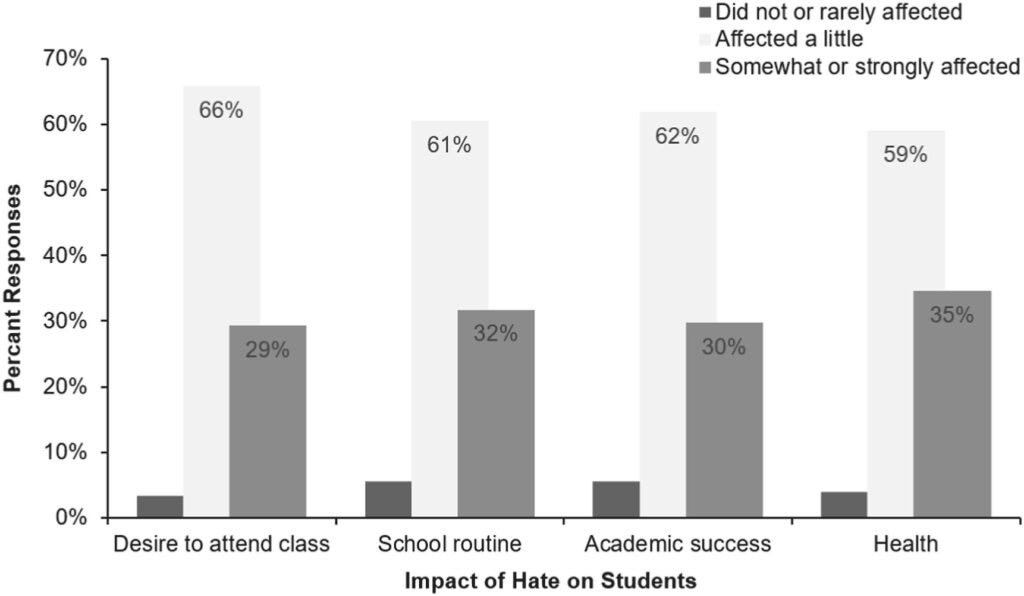

Questions about emotions following incidents revealed that over 60% of participants experienced one or more of the following feelings: fear, weakness, confusion, sadness, helplessness, pity, hopelessness, anger, and desire for revenge. While these reactions reflect serious psychological consequences, positive emotions such as self-confidence and pride in one’s identity were also reported. Interestingly, women generally reported fewer negative and more positive emotions than men. Regarding university perception, around 59% of participants considered hate a problem at their university. Approximately 80% reached out to the university or external support services. Among students who reported hate to the university, 66% stated that the university responded. However, only 26% of these students felt that sufficient measures were taken, while 40% felt the response was inadequate.

Concerning the regulation of online hate, 73% of students stated that the university should reprimand those who post hate online, while 70% believed that legal authorities should be involved in removing offensive content.

Universities must take active steps to protect all students

These results highlight several key findings, but most importantly, hate negatively impacts mental health, academic performance, and the sense of safety, while university responses are often insufficient. Therefore, the study also emphasizes the importance of developing preventive and educational measures within universities, including: scholarly panels dedicated to learning about the histories of their institutions, creating accessible reporting mechanisms, ensuring that students feel safe coming forward, allocating dedicated staff trained in culturally responsive practices, implementing meaningful policies and prevention strategies, training for university staff, faculty, and students, educating students on recognizing hate and providing support mechanisms, clarifying the difference between freedom of expression and hate, promoting spaces for dialogue, and continually evaluating policies and practices.

Ultimately, the study shows that both online and offline hate represent a serious problem and that universities must take active steps to protect all students. “We hope that this research will be an additional building block in mobilizing Canadian ministries of education and post-secondary institutions to think together and mobilize toward continually improving their mission to provide meaningful spaces for dialogue that foster knowledge and growth for all,” the authors concluded in the study.

Image: International Students, Study in Canada