Seeing the Person Behind the Screen: Supporting Oncology Patients Through Communication in the Digital Age

Every year, an increasing number of people receive a cancer diagnosis. Alongside medical treatment, another journey begins, often invisible but extremely important, the search for information and understanding of the disease. This is a diagnosis that brings uncertainty, fear, and many questions. Therefore, the treatment does not include only therapies and medical procedures; it also includes what we do every day as people: communication, and in the digital age, this almost inevitably includes searching for health information on the internet.

This part of the patient journey was at the center of a new study. The study, titled How does oncologists’ communication affect patients’ well-being and online health information seeking? – A randomized experiment was conducted by Tanja Henkel, Chamoetal Zeidler, Annemiek J. Linn, Julia C.M. van Weert, Ellen M.A. Smets, and Marij A. Hillen.

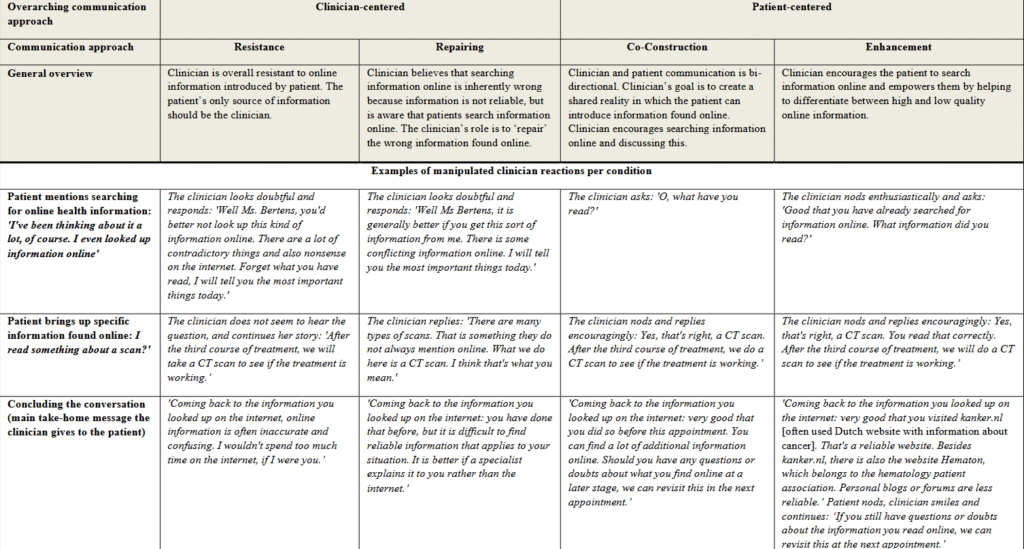

The researchers conducted the study by using a vignette methodology, which simulated medical consultations that allowed the study of communication in controlled yet realistic conditions. Participants took on the role of so-called analogue patients, meaning they imagined that they were the patient shown in the scenario and responded to the consultation from that perspective. After applying quality and inclusion criteria, the study included 270 participants who either had an active cancer diagnosis or had cancer in the past. Participants were mostly older adults (average age 61.6 years), and slightly more than half were women. The study used a between-groups experimental design. The doctor’s communication approach was systematically varied across four approaches: resistance to online information, correction with a warning about unreliability, joint consideration of information, and active encouragement of information seeking with recommendations of reliable sources. Scenarios were presented in video or text format.

The study results and the importance of the study

The results showed a clear advantage of the two patient-centered communication approaches. Participants exposed to these approaches were significantly more satisfied with the consultation and showed a greater intention to seek online information and discuss it during future consultations. On the other hand, the communication approach did not have a significant effect on anxiety levels or trust in the proposed treatment plan. The study also showed that communication does not affect all patients equally. Psychological characteristics, such as trait anxiety, intolerance of uncertainty, and tendency toward active information seeking, modified the effect of the communication approach. For example, patients with lower levels of trait anxiety showed greater willingness to discuss online information when exposed to patient-centered communication. As anxiety levels increased, this effect decreased. Similarly, patients who tolerate uncertainty better benefited more from a collaborative approach.

The importance of this study is particularly significant because it provides experimental evidence of the connection between physicians’ communication style and key patient outcomes. At a time when health information is more accessible than ever, the results suggest that the quality of treatment depends not only on therapies but also on how doctors talk with patients about the information they have already found. The study further highlights the importance of tailoring communication to patients’ individual psychological characteristics. In practical terms, the results suggest that doctors should view online information as an opportunity for dialogue, not as a threat to professional authority. Actively exploring what the patient has found, validating the patient’s effort, and guiding them toward reliable sources can strengthen the doctor–patient relationship and contribute to the quality of care.

About the study, we spoke with the corresponding author, Marij Hillen, an associate professor and Principal Educator at Amsterdam UMC. Her research focuses on communication between patients and physicians, with a particular emphasis on trust and the management of uncertainty in medicine. Marij Hillen is the author of over 65 international publications and has supervised numerous PhD and master’s students. She is actively involved in leading national and international professional associations on healthcare interaction.

Validating and guiding patients will help them use more reliable online sources

According to the study, “to date, research on the impact of online health information on cancer patients remains inconclusive.” How to change this? What is the key?

Marij Hillen: I think it’s important to recognize that both the type of online health information and its content and reliability can strongly vary. Therefore, how it affects patients may depend entirely on these factors. Also, what information patients seek and how they do so, changes rapidly. Consider, for example, the rapid rise of ChatGPT and similar AI-based tools. Therefore, it is key that researchers distinguish between different sources and formats of online health information. Additionally, they should recognize that the impact of online information may vary between individual patients and situations. In addition, better use could be made of the possibilities for recording online search behavior in real time, for example, by using eye tracking.

Do you think physicians’ age or digital literacy plays a role in how they respond to patients’ online information-seeking?

Marij Hillen: I don’t know of any research showing differences between physicians’ responses depending on their age or digital literacy, but we certainly see variation in how positively or negatively oriented to online health information clinicians are. In our recent (still unpublished) observations of oncological consultations, some clinicians would spontaneously raise the topic and encourage patients’ online searching, whereas others would not open up the discussion when they broached the topic. Our experimental findings indicate that facilitating patients’ online health information use is not necessarily time-consuming. Validating and guiding patients will help them use more reliable online sources and discuss what they read in future clinical encounters. This may save clinicians time in the long run, as they can then add to the information patients have already incorporated.

For clinicians to openly discuss online health information with patients requires moral virtues that are currently insufficiently highlighted

“The literature shows that some clinicians still hesitate to approach patients about online information because they fear that their authority might be challenged or that it might lead to new questions and extended consultations.” This part of the study also prompts me to ask whether university students today are sufficiently engaged in this topic, i.e., whether disagreements, differences of opinion, and multiple sources of information should actually encourage critical thinking in future doctors and explain everything necessary to the patient in an argumentative and empathetic way. Do you think current medical education sufficiently prepares future doctors to engage critically and empathetically with patients who have contradictory online information?

Marij Hillen: I think this is a very relevant question, as in my perception -not only as a researcher but also as a teacher of medical students- current medical education is lacking in two ways, at least in the Netherlands. First, for clinicians to openly discuss online health information with patients requires moral virtues that are currently insufficiently highlighted, such as curiosity (e.g., really wanting to know what the patient believes) and humility (e.g., being open to the possibility that the information a patient has found may add to, or even be more helpful than, the information you provide). Second, although clinicians are very aware that dis-and misinformation are now abundant, clinicians and teachers could benefit from effective techniques to address this in their clinical practice. The field of health policy communication has more experience in this area, and medical teachers might benefit from their expertise.

This study points not only to communication, but also to trust in the doctor. So I have to ask you this from a patient’s perspective: it seems to me that sometimes there can be a certain kind of shame in asking about or disclosing the correct source of information. For example, it may be easier to say “a friend told me” than “I saw on TikTok…”

Marij Hillen: I think I will reiterate two things I mentioned before: if a clinician is truly curious and humble, (s)he will not judge a patient based on where they got their information, but explore what the information entails, where it came from, and how the patient interpreted it. Eventually, the clinician can then still help the patient seek reliable online health information sources.

Being transparent about what we don’t know is exactly what drives our new knowledge acquisition

What misinformation in oncology worries you the most? What is the easiest thing for oncology patients to believe?

Marij Hillen: In a more general sense, I am very worried about how information that lacks any substantiation is presented as highly certain, for example, ‘using sun screen is dangerous’ or ‘castor oil will cure cancer’. In scientific research, doubt and uncertainty are inherent. Being transparent about what we don’t know is exactly what drives our new knowledge acquisition. But this also means that patients are often confronted with the many things clinicians (and science more broadly) do not, or cannot know. This is uncomfortable and requires tolerating uncertainty. If this uncomfortable feeling is replaced by misinformation that is presented as highly certain, that is dangerous, because it will be highly attractive to patients. It also means that in the long run, people will become less able to manage uncertainty, and the clinicians and researchers voicing that uncertainty.

“Rigorous experimental research is lacking to determine the causal effects of oncologists’ approach to online communication of health information on patients’ emotional well-being and behavior.” Looking globally, is this a problem, because if there is not enough research, even though we are not dealing with this topic enough, we somehow cannot understand the problems more deeply?

Marij Hillen: I think this is a problem, particularly because clinicians and educators want to see ‘solid’ evidence on the importance of effective communication about online health information. Simply arguing that it matters for patients’ well-being and consultation effectiveness is not enough. Our experimental study provides strong evidence for the impact of communication, which is a first step to improving clinical practice and, eventually, patient wellbeing.

Every patient and situation requires the clinician to tailor their communication approach

If we look at the broader picture of oncology patients undergoing long-term treatment, fears also have a psychological impact, which means that in that potential case, the patient sometimes does not want to believe what the doctor is telling them, even though the doctor has access. It seems to me that your study points to many things and would be useful in many ways, so I have to ask you what is the most difficult aspect when it comes to applying the results of a study like yours in practice?

Marij Hillen: I think what you are mentioning here is exactly the challenge in applying our results into practice. Overall, I think our study convincingly shows that clinician communication matters when it comes to online health information. But it mainly shows a general effect, whereas the optimal approach to communication will in practice often depend on the patient’s specific situation, emotional state, needs at that moment, and abilities. In our teaching, clinicians understandably ask for concrete tools to address all of those different aspects. But there is no one-size-fits-all, which means that every patient and every situation requires the clinician to carefully explore and attempt to optimally tailor their communication approach to the patient. That is not an easy task, but it can result in more meaningful conversations and relationships with patients.

Focusing on Europe, what do you think we could improve in Europe when it comes to cancer information?

Marij Hillen: I think in general that a lot of health information is extremely complex. This is not only the case for written information, but also something we see in our observations of clinician-patient interactions. There is still a mountain of work to do in simplifying written information and in supporting clinicians in tailoring the focus and complexity of their information to patients’ needs and abilities.

The study lays a foundation for understanding this often overlooked aspect of the patient experience

Across the world, hundreds of thousands of people undergo treatments, receive diagnoses, and attend medical consultations. As current or former oncology patients, they often go through a largely invisible journey: sitting at a computer or using their phone in search of information that can provide hope, guidance, or relief, but which can also be misinformation or simply experiences that do not apply to their situation. This study clearly demonstrates and lays a foundation for understanding this often overlooked aspect of the patient experience.

In front of physicians and future doctors are individuals who, at their core, seek more than just facts and advice. They seek an understanding of the fear, uncertainty, and emotional challenges they are experiencing. A patient-centered communication approach, which recognizes their efforts and guides them toward reliable sources of information, can bridge this gap and transform online information from a potential source of confusion into a tool that builds trust. Recognizing and addressing the human experience behind every question, every search, and every consultation is crucial for improving the quality of care and fostering meaningful doctor–patient relationships.

This study reminds us that, in the digital age, patients are looking not only for information but also for empathy, understanding, and support, precisely what effective communication can provide.

Photo courtesy of Marij Hillen, corresponding study author.

Funding: This research was funded by the Dutch Cancer Society (KWF), project number: 12760.