Global economy doubles, but poverty persists

Speed read

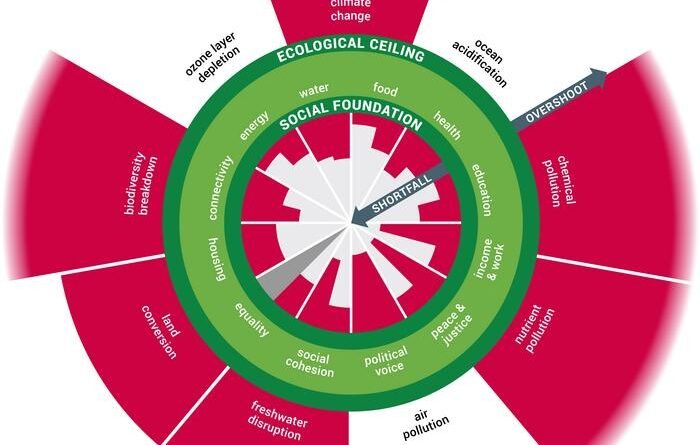

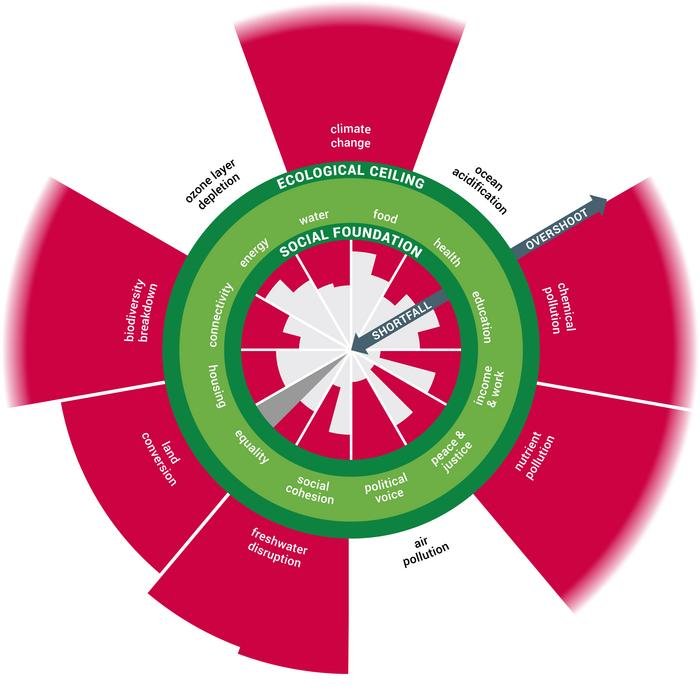

- The “Doughnut” diagram shows the safe zone between the social foundation, where people meet their basic needs, and the ecological ceiling, beyond which human activities harm the planet.

- An analysis of 35 indicators from 2000 to 2022 reveals that rich countries contribute the most to environmental damage, while poor countries suffer the most from a lack of basic resources.

- The richest 20% of countries are responsible for more than 40% of environmental overshoot, whereas the poorest 40% suffer from over 60% of global resource shortages.

- Research indicates that economic growth alone does not improve the lives of all people, highlighting the need for new models of progress that reduce social deprivation and ecological overreach.

A new study shows that while the world economy more than doubled between 2000 and 2022, billions of people still live without basic necessities. According to data, 3.4 billion people still do not have safe, managed sanitation, and 1.7 billion people still do not have basic hygiene services at home. On the other hand, human activities are rapidly exceeding the safe limits of the planetary systems that support life on Earth.

The study titled, “Doughnut of social and planetary boundaries monitors a world out of balance” was published this month. The study authors are Andrew Fanning, Research & Data Analysis Lead at Doughnut Economics Action Lab (DEAL) and Visiting Research Fellow at the Sustainability Research Institute at the University of Leeds, and Kate Raworth, co-founder of DEAL and Senior Teaching Fellow at the Environmental Change Institute at the University of Oxford.

“We investigate inequalities in our global results by differentiating three broad clusters of countries with available data—the poorest 40% of countries, middle 40% of countries, and richest 20% of countries—based on average national income per capita across 193 countries over the 2000–2022 period,” they wrote in the study.

We spoke with the corresponding study author, Andrew Fanning.

What is the doughnut frame?

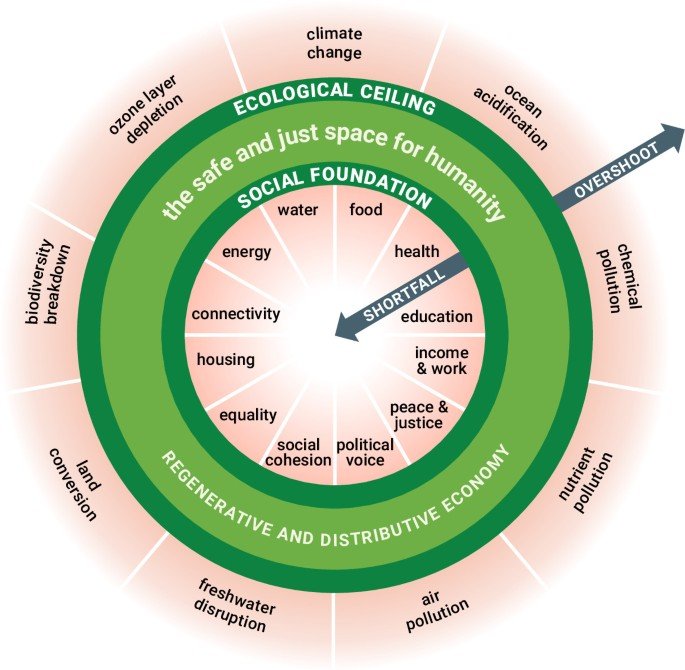

As the scientists explain in their study, the doughnut frame consists of the space between two concentric rings. The inner ring represents the social foundation, below which lies critical human deprivation, and the outer ring represents the ecological ceiling, beyond which lies critical planetary degradation. While between these two rings lies a doughnut-shaped area that limits humanity’s ambition in the twenty-first century to protect the stability of our planetary home while ensuring that no one fails to meet their essential needs. It should be noted that this framework was created in 2012 and then updated in 2017, as the study explains, to reflect developments in the understanding and measurement of critical human deprivation and planetary degradation.

“Here we propose a third iteration of the global Doughnut, with a revised set of 21 dimensions, measured by 35 indicators of social shortfall and ecological overshoot. We also present our efforts to transform the Doughnut from being a static snapshot in a single year to an annual monitor of global social and ecological health in the twenty-first century, by incorporating time-series data from 2000 to 2022 for as many indicators as possible,” the scientists state in the study. They further state that it is important to note that the global population of “humanity” depicted in the doughnut is not a single entity.

The study: If human progress this century depends on eliminating social shortfall and ecological overshoot simultaneously our latest synthesis underscores that the world is still far from securing it.

The First Annual Global ‘Dashboard’: Analysis of 35 Indicators from 2000 to 2022 Using a ‘Doughnut’ Framework

Researchers have created the first annual global “dashboard” that tracks trends in social deprivation and environmental overshoot in the 21st century. It shows that rich countries are contributing the most to environmental overshoot, while poorer countries are suffering the most from the lack of basic resources. They analyzed 35 indicators from 2000 to 2022 using a “Doughnut” framework that combines social and planetary boundaries. Global GDP has more than doubled, but reductions in poverty, hunger, ill health, education, and housing shortages have been modest. If current trends continue, the UN’s 2030 goals will not be met.

This means that while the world economy has grown rapidly – global GDP (the total value of all goods and services) more than doubled between 2000 and 2022 – progress in improving people’s lives has not kept pace. In other words, economic growth has not automatically led to poverty reduction or improved living conditions for all. Ecological overshoot is worsening, with humanity exceeding at least six of the nine planetary boundaries by 2022. Repairing the damage requires halting and reversing course twice as fast as current rates of degradation.

The study also highlights huge inequalities: the richest 20% of countries (15% of the world’s population) are responsible for more than 40% of ecological overshoot, while the poorest 40% (42% of the population) suffer more than 60% of global shortfalls. Those with more resources contribute disproportionately to ecological damage and experience less deprivation, while those with less resources contribute little to planetary degradation but experience far more deprivation.

“Our Analysis underscores a need to continue deepening research into post-growth economic futures, especially in high-income countries. The data underpinning our analysis can serve as an input into ecological macroeconomic modeling that seeks to assess policy options with the potential to decouple human well-being from both ecological overshoot and economic growth…Given the urgency of completing the shift to a new pattern of progress, we intend to continue refining and measuring the Doughnut on an annual basis, so that it may serve as a continually relevant and up-to-date monitor of social and ecological trends,” scientists explain in the study.

“In our view, the latest global Doughnut results offer insights for decision-makers and practitioners by helping to redefine economic progress by moving beyond a narrow focus on GDP growth.”

Does this mean that there have been no major changes in behavior or in our attitude, not only towards the environment but also towards those who are most exposed to the risk of, say, poverty?

Andrew Fanning: At the global scale, we do find reductions in the share of population experiencing deprivation across most of the social indicators that we analysed, which is good news. However, the not-so-good news is that current rates of progress fall far short of what would be required to eliminate such poverty and deprivation by 2030, as agreed by the world’s governments in the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals. When it comes to planetary degradation, we find very little good news, unfortunately, with most ecological indicators worsening except for the notable exception of ozone layer depletion, which has been slowly recovering since the mid-1990s with thanks in large part to effective global regulations.

How can these results help decision-makers, and how can we use them in practice?

Andrew Fanning: In our view, the latest global Doughnut results offer insights for decision-makers and practitioners by helping to redefine economic progress by moving beyond a narrow focus on GDP growth. The Doughnut combines a set of social and ecological dimensions into a coherent, visual dashboard that monitors human well-being and planetary health on their own terms. By making visible the current trajectory away from – rather than towards – eliminating global social shortfall and ecological overshoot simultaneously, our results show the pursuit of economic growth has been failing to bring humanity into a safe and just space.

Instead, we see an urgent need for decision-makers, researchers, and practitioners to explore policies and practices that overcome nations’ dependence on GDP growth so that they can instead reorient towards ecologically regenerative and socially distributive outcomes. Crucially, such reorientation must acknowledge country-specific differences, especially given the disproportionate contribution to planetary damage by the richest, and the disproportionate share of population in deprivation among the poorest.

Of course, we are aware that up-to-date monitoring of social and ecological trends will not, in and of itself, transform the dominant growth-based approach to economic policymaking. Instead, we see this information flow as an additional tool that practitioners can use to push for transformative action in their places and institutions. For example, a strategy we have been pursuing together with colleagues at Doughnut Economics Action Lab is to convene and make visible a global community – currently more than 10,000 members worldwide – that is collectively experimenting to put the concepts of ‘Doughnut Economics’ into practice in many diverse ways and distinct contexts, by reframing economic narrative, engaging in strategic policy influence, collaborating with like-minded innovators, and crucially, sharing back lessons for iterative learning.

On the question of whether these challenges can be addressed, and how long it might take, Fanning concludes: “The question of what will be most difficult or easier is very hard for me to answer because our results show different priorities across countries and contexts. In the poorest countries, which contribute little to global ecological overshoot, there is a clear need to reduce poverty by improving social provisioning infrastructure. Meanwhile, in the richest countries, we find an urgent need to reduce resource use to sustainable levels, while maintaining or improving social outcomes.

So I believe transformative action is needed within all countries, and also between them. Can this be done, and how long will it take? Nobody knows, and I must say current trajectories are highly concerning, but there are also many examples of local, national, and international initiatives working collectively to shift the economic focus away from endless growth and towards ensuring human well-being and planetary health this century – and I am proud to stand with them.“

Image: Global social shortfall and ecological overshoot. Fanning and Raworth (2025)