Can Vulnerable Residents Easily Reach Barcelona’s Climate Shelters?

Extreme heat is becoming an increasingly serious health risk in Europe, with the summer of 2024 breaking several temperature records. A study by the Barcelona Institute for Global Health (ISGlobal) estimated that around 62,775 deaths in Europe between June and September 2024 were linked to high temperatures. The heat is particularly dangerous for older adults and low-income residents, highlighting the urgent need for public health measures and safe spaces.

A recent study by Serena Mombelli, Roger Gonzàlez March, Fernando Cucchietti, Oriol Marquet, and Patricio Reyes, entitled “Are Barcelona’s climate shelters accessible to vulnerable residents? A mobility justice analysis”, examines how shelter location and neighbourhood conditions affect whether these vulnerable groups can actually reach them during extreme heat.

We spoke with Serena Mombelli, corresponding author at the Department of Geography, Autonomous University of Barcelona.

About the study

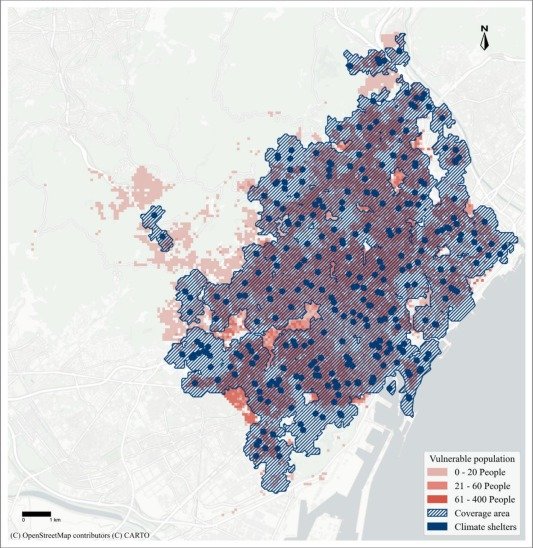

Due to climate change, cities worldwide are facing an increasing risk of extreme heat waves, which particularly affect vulnerable groups such as the elderly, low-income populations, and migrants. In Barcelona, the city addressed this issue by establishing the Climate Shelter Network in 2019. This network includes more than 350 facilities, ranging from public buildings, such as schools and libraries, to open spaces like parks and gardens. The city aims to ensure that by 2030, all residents live within a five-minute walk of a shelter. While the infrastructure is substantial, the issue of equitable access remains.

The study investigates how the spatial distribution of shelters and the socioeconomic characteristics of neighborhoods influence inequalities in access for vulnerable groups. The authors formulated two hypotheses: reduced mobility and limited shelter availability, due to the slower walking speed of older adults and the seasonal closure of facilities, significantly restrict access for vulnerable populations; unequal access is exacerbated by socioeconomic conditions in urban neighborhoods, where low income and high proportions of migrants create overlapping vulnerabilities.

The Barcelona Climate Shelter Network was used as a case study. The researchers combined spatial analysis (GIS) with demographic data. Vulnerable populations were defined as adults aged 65 years and older, with walking speed adjusted to 3.28 km/h to realistically model accessibility for older adults. Access to shelters was measured as a ten-minute walk, taking into account terrain, pedestrian networks, and the shelters’ opening days. Socioeconomic factors included household income and the proportion of foreign-born residents.

The results show that approximately 92% of vulnerable residents live within a ten-minute walk of a shelter. However, during August, when many shelters are closed, coverage drops to 75%, confirming the first hypothesis regarding the impact of reduced mobility and accessibility. The second hypothesis is supported by findings showing that neighborhoods with lower incomes and a high proportion of migrants, such as Sants-Montjuïc, Nou Barris, and Sant Andreu, have significantly lower access to shelters compared to wealthier or more central areas. An exception is Ciutat Vella, which provides universal access despite socioeconomic vulnerabilities.

Rising rents push vulnerable residents to Barcelona’s outskirts

“Barcelona launched its Climate Shelter Network in 2019, which includes more than 350 facilities. However, there is limited evidence on whether these shelters are equitably accessible to those most at risk.” This is a very important question, but I am interested in how much housing prices have an impact in this case. Specifically, when climate shelters were discussed, was that factor also considered? I also notice that there is increasing discussion about housing prices and apartment rentals — does all of this put additional pressure on Barcelona?

Serena Mombelli: Climate shelters are essentially public spaces, such as schools, libraries, and community centres, which the city adapts to provide relief during the hottest and coldest months of the year. From what I can tell, the dynamics of housing weren’t really considered when deciding which buildings would become shelters, but they probably should have been. While the study did not directly examine housing prices, it is difficult to separate the two issues.

As rents and property prices continue to rise in Barcelona, many low-income residents and migrants are being forced to move to the outskirts, where there are fewer shelters and they are more difficult to access. Then there’s the question of energy poverty: when people spend more of their income on rent, there’s less left for heating or cooling, and many homes in low-income and migrant-dense neighborhoods aren’t well insulated. This means that even more people may need to rely on public shelters to get through heatwaves or cold spells. In the end, housing and climate resilience are closely linked; both determine who gets to stay safe and comfortable during extreme heat or cold.

“The Barcelona City Council has set a target to ensure that by 2030 all residents have a climate shelter within a 5-minute walk of their home.” What is the biggest challenge in your opinion?

Serena Mombelli: The biggest challenge is not only converting more buildings into shelters but also ensuring that they remain accessible and operational throughout the summer. Many community centres, for example, close during the summer, ironically, when people need them most, reducing coverage to 75% of Barcelona residents. Furthermore, we need to consider mobility justice: people move at different speeds and have different accessibility needs, so not everyone can reach a shelter in the same way. Therefore, even if a facility is technically nearby, it may still be out of reach for some people. The uneven distribution of resources and infrastructure across the city shows that achieving universal access is not only a technical challenge but also about equity and inclusion. These principles must be incorporated into policy and planning decisions.

Barcelona shows that having a lot of shelters is not enough

“Barcelona was chosen because it is a pioneer in climate shelter programmes in Europe, and because its current policy aims to ensure that all residents can access a shelter within a 10-minute walk.” How can the findings of your study and Barcelona’s experiences inform and support the development of climate shelter programs in other cities?

Serena Mombelli: Barcelona shows that having a lot of shelters is not enough. The location, accessibility, and opening hours of shelters all matter just as much. Other cities can learn from this by using a combination of climate data, mobility patterns, and social indicators to determine the optimal distribution and opening hours. The study also highlights the importance of focusing on vulnerable groups, such as older adults, migrants, and low-income residents, rather than just planning for the ‘average’ person. Barcelona’s mapping approach could provide a valuable model for other Mediterranean cities such as Rome and Athens, which face comparable heat-related challenges.

“There is often insufficient evidence to determine whether heat-vulnerable populations have adequate proximity-based access to climate adaptation strategies such as climate shelters.” Could this pose a problem for the research?

Serena Mombelli: Yes, it can be a problem, especially for evaluating the success of these initiatives. Without sufficient data, it is challenging to determine whether adaptation measures are effectively protecting the most vulnerable individuals. While many cities have maps of shelters or public cooling spaces, there is often insufficient information about who uses them and how accessible they are to vulnerable groups. This limits the effectiveness of these programmes. The study attempts to address this issue by combining spatial and demographic data, an approach that could be replicated in other contexts.

Not knowing where shelters are can put newcomers at risk

“Disparities are also apparent among foreign-born populations, with only around 85% having access to a shelter within a 10-minute walk, compared to 92% of the general population.” When it comes to foreigners, how much does the fact that they may not know the city well impact their access or experience?

Serena Mombelli: That’s a really important point. For migrants and newcomers, not knowing where the shelters are, or even that they exist, can have a significant impact. Language barriers and limited access to local information can reduce the effectiveness of the system. For example, a study in Barcelona by Amorin-Maia et al. (2023) looked at over 200 public spaces designated as climate shelters and found that the intersecting vulnerabilities of marginalised populations, such as low-income residents, migrants from the Global South, and women, were often poorly addressed.

Housing inadequacy and energy poverty made these groups the most affected and least able to cope with extreme temperatures. This is why communication and outreach are so important. Cities could provide shelter information in multiple languages, integrate it into navigation apps, or collaborate with local associations to raise awareness. Having shelters is not enough; we must also ensure that those who need them most know how to use them and can get there safely.

“While these findings suggest that Barcelona’s climate shelter network effectively offers access to most of its population at risk of heat-related health issues, the spatial analysis also highlights significant gaps that require further attention. Furthermore, additional research is required to investigate sociodemographic factors, such as gender, income level, and migrant status, that could increase susceptibility to extreme heat. These intersecting vulnerabilities could lead to unequal exposure and limited access, which could exacerbate existing social inequalities.” Are these shortcomings easily addressed?

Serena Mombelli: Some challenges, such as keeping shelters open for longer or ensuring that more are available in August, could be resolved fairly quickly through better coordination between city departments. However, deeper issues, such as those related to income, housing, or migration status, are much more complicated. Addressing these requires long-term policy work such as investing in affordable housing, improving transport options, and carrying out genuine community outreach. Therefore, while some solutions are logistical, others are social and structural, and both require attention.

Make cities safer, fairer, and more resilient for everyone

“Achieving full accessibility will therefore require strategic planning, expansion of the shelter network, and extension of opening days, especially in underserved, socioeconomically disadvantaged areas.” This requires urban planning, financial investments, and community engagement. Is the level of community engagement at a good level?

Serena Mombelli: Some districts in Barcelona are doing really well, but access to shelters remains uneven. They are signposted, but not everyone knows about them. Community engagement has increased through neighbourhood associations and social programmes, but participation varies from area to area. It is crucial to get communities involved, both to decide where shelters are needed and to ensure that people actually use them. When local networks are strong, shelters become more than just emergency spaces; they become real community assets. There are projects within the Autonomous University of Barcelona that specifically consider the inclusive planning and community engagement of urban climate adaptation strategies. For instance, IMBRACE (Embracing Immigrant Knowledges for Just Climate Health Adaptation).

What do you hope your study will achieve by next year?. What are the next steps?

Serena Mombelli: Looking ahead, I hope that this study will help to refine the way in which Barcelona, and, hopefully, other cities, plan and manage their climate shelter networks. Ideally, by next year, the findings will be used to inform decisions on where new shelters should be located, when they should be open, and how accessibility can be improved, particularly for the most vulnerable groups.

I would also love to see this approach being adopted in other cities, because each city faces its own version of these challenges. One interesting addition would be to include tree coverage data, essentially mapping how shaded the route to a shelter is. This would provide a much more accurate indication of comfort levels and exposure during periods of extreme heat. The next step is to build on this analysis by expanding it to other European cities and integrating environmental and social data, so that adaptation policies can be truly inclusive. Ultimately, the goal is simple: to make cities safer, fairer, and more resilient for everyone.

This study shows that having many shelters alone is not enough to protect vulnerable residents during extreme heat. Accessibility depends not only on distance but also on mobility, neighborhood conditions, and socioeconomic factors, including housing pressures. The study by Mombelli and colleagues emphasizes the importance of planning shelters with a focus on equitable access, which is crucial for making cities safer and more resilient for everyone.

Image: Climate refuge created at the Plaça del Coneixement, UAB