Sniffing Out Trouble: How Dogs Track Invasive Carp

Pet dogs trained at the University of Waikato can detect carp in water samples with accuracy comparable to advanced DNA tests. Experiments showed they could identify carp in tanks, natural lakes, and even unfamiliar environments, demonstrating the dogs’ ability to generalize their scent detection skills.

Dogs can detect more than just dinner; they might also help track invasive fish. Researchers at the University of Waikato trained Labrador Retrievers, and one Labrador-Border Collie cross, to sniff out carp in water samples. They wanted to see whether canine noses could rival environmental DNA (eDNA) analysis, a technique used to identify species in water. The authors of the study “Dogs can detect carp (Cyprinus rubrofuscus) using lake water samples” are Melissa A. Collins, Samuel Barclay, Clare Browne, Nicholas Ling, Grant W. Tempero, Ian Kusabs, and Timothy L. Edwards.

According to the study, introduced carp (Cyprinus spp.) have caused significant damage to freshwater ecosystems worldwide. “Early detection of carp invasions increases the chances of successful eradication; however, current detection methods are resource-intensive,” they warn. We spoke with Timothy L. Edwards, a behavioural psychologist, the corresponding author of the study, and director of the University of Waikato’s Scent Detection Research Group.

About the study

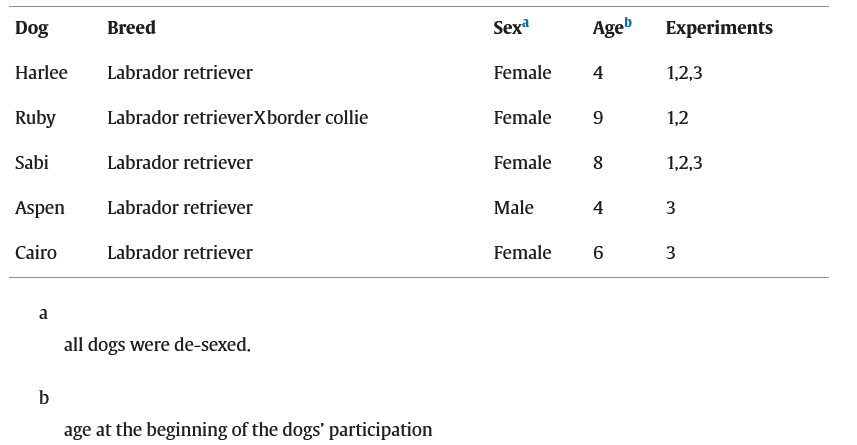

The team collected water from tanks containing adult carp, as well as control tanks without fish. Samples were then stored under sterile conditions until testing. The team also gathered water from a variety of natural lakes across New Zealand, including both carp-inhabited and carp-free sites, covering a range of nutrient levels from oligotrophic to hypertrophic. As explained in the study, pet dogs were recruited for this project via word of mouth, social media, and posters. “Behavioural characteristics, including dog arousal levels in the laboratory, motivation to work for food, and initial training progress, were evaluated to determine each dog’s suitability for this research. Of 15 dogs evaluated, four desexed females and one desexed male between four and nine years of age met the participation criteria and took part in this study,” the scientists wrote.

Experiments: From Tanks to Lakes

Experiment 1: Canines versus controlled carp scent

In the first experiment, dogs were presented with 17 water samples per session, seven containing carp and ten controls, to test their ability to detect a standardized carp biomass of 310 kg/ha. Depending on the dog’s motivation to work, each dog completed 4–6 sessions per day, with a 5-minute break between sessions. The results showed that dogs correctly identified carp-laden samples.

Experiment 2: Detecting carp in the wild

Next, the dogs were challenged with samples from lakes with natural carp populations and lakes without carp. Surprisingly, the dogs performed better at identifying samples from previously unknown lakes than those they had already been familiar with, suggesting they could detect carp scent independently of other environmental cues.

Dogs versus DNA

Meanwhile, eDNA tests were run on the same samples. Multispecies metabarcoding picked up carp in three out of five known carp samples, while the more precise qPCR method confirmed carp presence in almost all lakes with established populations. Overall, the dogs’ performance matched the reliability of qPCR.

Experiment 3: New environments

Finally, four dogs were tested on water from 24 lakes, half with carp, half without, to see if they could generalize their detection skills. They correctly identified carp in most samples, with an average sensitivity of 86% and specificity of 65%. These findings suggest that trained dogs can detect carp even in unfamiliar lakes.

Scientists have also trained a different group of dogs to detect another invasive species

How did you come up with the idea for this study?

Timothy L. Edwards: I developed an automated machine that dogs can operate independently to be trained and used for scent-detection work in laboratory settings. Because the apparatus can be used with nearly any sample type, I discussed with my colleagues in freshwater ecology what samples could be brought to the lab from the field for conservation detection work, and we agreed that it may be possible to use water samples to test for the presence of target fish species.

How significant are the results of the study or, say, applicable to other invasive species?

Timothy L. Edwards: We have also trained a different group of dogs to detect catfish (another invasive species) and got very similar results. This suggests that our system/approach is applicable to other aquatic species as well. The findings are significant because they suggest that scent-based monitoring for invasive aquatic species (with dogs or potentially analytical chemistry approaches) may be possible; in combination with other monitoring/confirmation tools, such as eDNA, this could improve the efficiency (cost-effectiveness) and accuracy of monitoring activities.

Happy Dog, Sharp Nose

What was it like working with the dogs in this case? Were they always willing to cooperate?

Timothy L. Edwards: We only worked with dogs who were interested in interacting with the machine and working for treats. All of the dogs in the study were enthusiastic about participating (their owners would tell us of their excitement when they were being taken to the dog lab).

“Despite these advantages, there are limitations with the pet dog approach. For example, in our study, most owners could only bring their dog into the laboratory twice per week, limiting the frequency of training and testing sessions.” Could it be assumed that this low frequency, while limiting training, might have made the sessions more interesting for the dogs? How important are the dogs’ concentration and motivation, and is it possible that this schedule reduces their stress or pressure during task performance?

Timothy L. Edwards: This is a great question; there is a little bit of information on training frequency, which indicates that training too frequently can slow down learning of the task; we didn’t mention this, but, indeed, the fewer training days each week may not have been a limitation.

Given the results these dogs have demonstrated, could this approach provide benefits to the dogs and their owners in the future? How do you plan to apply this knowledge moving forward?

Yes, in our experience, participating in this task was a form of enrichment for the dogs. The owners were happy to participate because it was a bit like taking their dog to “doggy daycare,” but also allowing their dog to learn some new skills and use their brain in the process. We think that this system using pet dogs could even be applied in an operational system if we or someone else ends up using this system operationally.

From Fish Pheromones to Favorite Experiments

For example, during spawning, carp secrete reproductive pheromones, so how persistent is the scent of carp? Are there any factors that could affect this?

Timothy L. Edwards: Yes, this is a good observation; the scent profile of the fish could change over the seasons. We reasoned that training dogs on the fundamental fish odour (a combination of secretions that have been released into the water under normal conditions) should provide a persistent underlying target profile for them to identify, even if other odours are present, but this is something that we have not yet tested experimentally.

Which experiment is your favorite?

Timothy L. Edwards: The final experiment is a very important one in my view because it is most informative about the operational viability of this system, so this is my favorite one.

Seventeen Samples and a Spinning Plate

“The automated scent detection apparatus allowed the dogs to work without a handler being present in the room, mitigating potential issues associated with human cueing and subjectivity. Briefly, water samples were placed in 17 individual segments on a 1 m diameter circular stainless-steel plate, which rotated on a carousel.” Out of curiosity, why 17?

Timothy L. Edwards: This number came about due to the dimensions of the apparatus, the optimal size of the segments, and some size limitations on the apparatus (to keep it small enough to fit through doorways, etc.). There is no “correct” number of trials for scent-detection training and testing sessions, but this number falls in the range of commonly used trial numbers and seems to strike a good balance of being large enough to allow the dog to do quite a bit of work in one session, but not so much that they become fatigued or satiated.

When it comes to further research, what new question do you have after the results of this study?

Timothy L. Edwards: I think that the key next steps would involve sorting out a few more operationally relevant details, like determining if the dogs can maintain high performance even if they sometimes don’t get feedback when they are correct. This is necessary if the system will be used operationally because the status of samples that need to be evaluated will not be known, and we cannot assume that the dog is correct (rewarding incorrect indications can very quickly lead to loss of accuracy). Additional research on the dogs’ performance with a variety of “real-world” water samples would also be very helpful in determining the reliability of their performance and potential influences of other factors that might impact the scent profile of the samples (like water quality variables).

Whether following the scent of a favorite snack, a cherished toy, or the trail of invasive carp in New Zealand’s lakes, these canines demonstrate just how extraordinary a dog’s nose truly is.

Image: Cairo, Fish Project. Scent Detection Research Group (SDRG)

This work was supported by the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (grant number UOWX1805).